The final croak

September 30, 2013 § 10 Comments

A dark day in the sun

The heron ate my frogs.

Not “a heron”, but “the heron”. In Ireland, serious threats are accorded the definite article: the fox, the blight, the whooping cough, and — on that fine day last spring — the heron.

Or rather, it was a fine day for the heron, but not so for the frogs. They had already had a stressful year. Spring had come early, and gone away again. January was so mild that the frogs had spawned on the 7th (the earliest date yet in my twenty-one-year stint in this garden). They spawned again at the end of the month, and then, spring retreated and winter blew back in with flurries of sleet and snow.

When spring finally reappeared in March, they were in the pond again — glorious, tumbling bundles of fornicating frogs. I left them to their work, undisturbed by my camera. After the difficult start to the year, they deserved some privacy and peace.

The heron thought otherwise.

My phone rang. It was a neighbour: “Are you looking out the window?”

No, I wasn’t (for once).

“There is a huge bird eating the frogs — like a crane or something. It’s amazing!”

I was torn: should I reach for my camera, or should I shout at the dogs to scare off the intruder? A quick look out the window revealed that it wasn’t a crane (a very rare visitor to Ireland), but — as I suspected — a grey heron (Ardea cinerea), the largest heron in Europe, which is native to Ireland, Britain and much of Europe and to parts of Asia and Africa. My glance revealed also that it was too late for the frog, dangling darkly from the bird’s brutal bill, so I grabbed the camera.

I felt like a traitor towards the amphibians with whom I had shared many summer afternoons by the tiny pond, but I wanted the picture. I am, after all, keen on wildlife, and here was wildlife — and wild death — happening right in front of my lens. Still, I felt affronted and angry. I had nurtured the frogs, thinking of them as “my” frogs, although they were nobody’s frogs but their own. But now, it was apparent, they were the heron’s.

The frog that was in the heron’s bill, and that would soon be in its stomach, was old enough to breed, so it was three or four years old. What a way to go. One minute in the throes of reproduction, and the next in the jaws of death.

I moved closer and closer to the heron. Was there a touch of annoyance in its golden, predator’s eye? Eventually, it unfolded its massive wings and flapped off to perch on a tree in a neighbouring garden, the frog still hanging from its bill.

It swallowed it whole (and still alive?), and moved to the top of a swing set, perhaps contemplating its next move. Would it be able to cram in another frog? It was the heron’s own breeding season, so perhaps it was stocking up on food to regurgitate later for its chicks. A magpie arrived, sat next to it on the wooden bar, and then dive-bombed it several times. Maybe the magpie, a ruthless predator itself, was worried what might happen to its future offspring if the heron got too comfortable in this place.

The big bird came back to rest on the wall of my garden, but I saw it off too. I felt mean scaring it away, but it had already helped itself to several frogs. I thought it would probably be back before I managed to get some netting for the pond.

And indeed it was: a while later it was swishing its yellow bill around in the weedy water, as if stirring a pot of porridge. After I had rigged up an unlovely wire grid over the pond — with room for songbirds and frogs to scoot under — the heron returned several times, puzzled at this barrier to its food source. It sat on the greenhouse roof (where it made a striking finial ornament), waiting to see if the wire mesh might somehow disappear. It didn’t. In making the pond inviting for the frogs, I felt I had a duty of care for them. The heron, I decided, could go somewhere else.

Ménage à Trois (or even quatre)?

April 21, 2011 § 5 Comments

The dunnock is a small, brown bird that creeps about on the ground, foraging for insects and creepy-crawlies. Its plumage is drab and puritanical, and its movements, are — for the most part — those of a preoccupied old lady, shuffling down to the shops for a loaf of bread and a pint of milk.

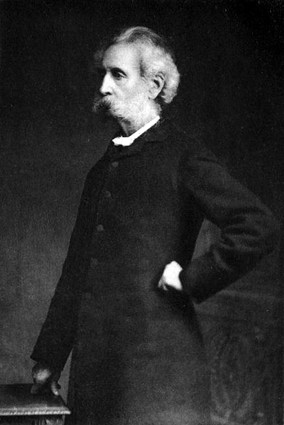

Its apparent modesty and decency prompted the Victorian ornithologist, the Reverend Frederick Orpen Morris, to preach to his congregation that they would do well to emulate the dunnock: “Unobtrusive, quiet and retiring, without being shy, humble and homely in its deportment and habits, sober and unpretending in its dress, while neat and graceful, the dunnock exhibits a pattern which many of a higher grade might imitate, with advantage to themselves and benefit to others through an improved example.”

Morris was born in Ireland, near Cork, the son of a British admiral and his wife, Rebecca Orpen, who was the daughter of the vicar of Kelvargan, in Co Kerry. After attending Oxford and taking Holy Orders, Morris was posted to various parishes in Yorkshire. He was a serious amateur ornithologist and entomologist, publishing many essays and pamphlets, and editing and revising several books. Despite his great output and dedication, it is the quotation above that is most often wheeled out by writers today. And with some glee.

The dunnock is, in fact, anything but unobtrusive and retiring, and its habits are hardly humble or homely. The dunnock is — oh, Reverend Morris, if only you had known! — mad for sex. Arrangements where a female is mated with two males are not unusual. Or sometimes (less frequently) a male has two females. Or sometimes there is even a spot of avian swinging, where two pairs mix and match.

I’m put in mind of this because for the past couple of weeks there has been a great amount of dunnock activity in our garden. And very little of it includes shuffling about on the ground looking for food. Instead, there are three birds dipping and diving, fluttering (and, I presume) flirting. The sexes look the same in this species, so it’s not easy to tell males and females apart. But, judging from the way that one bird (the beta male?) frequently skulks just out of sight, I suspect that we have the more usual dunnock ménage à trois of one female and two males.

According to N.B. Davies in Dunnock Behaviour and Social Evolution (Oxford University Press, 1992) females “made life difficult for an alpha male by actively attempting to escape his close attentions and by encouraging the beta male to mate!” And later he describes that “On several occasions I saw females hiding away with the beta male under a hedge or bush. When the alpha male came by searching for them, they crouched down and remained motionless until he had passed by.”

Why would the female dunnock want to mate with more than one male? Well, it seems that it’s for the survival of her brood. When a female is raising her chicks, a male will help to feed them only if he has copulated with her earlier. So, it makes sense for her to have two regular partners, even if it means scooting off into the bushes with Beta while Alpha is looking the other way.

As for the males’ motives: obviously they want to mate with as many females as possible in order to ensure the survival of their genes. Their mating approach is unusual, to say the least. I’ll let N.B. Davies put it into words: “The act of copulation itself is extraordinary, with a male pecking the female’s cloaca carefully for a minute or so before he mates.” The reason? So that she ejects the sperm of her previous mate. In the dunnock world there is a veritable orgy of copulating, as male birds compete for paternity. Nature, therefore, has given Reverend Morris’s “quiet and retiring” dunnocks particularly large testes: they weigh 64 per cent more than those of most birds of their size, and have sperm reserves about 1,000 times greater.

Those Damn Dawn Birds

April 6, 2011 § 11 Comments

I love the birds, I really do. But this morning they woke me up with their break-of-day hollerings. They woke me up yesterday too. And they are probably going to wake me up every single dawn for the next month or two.

This morning, I recorded 30 seconds of their uproar: which you can hear here:

It sounds considerably sweeter now than it did at 5.59am.

But when I think that this may have been one of the participants (born and reared in a tangle of honeysuckle):

And that this may have been another: “Oscar” (all our robins are called Oscar):

I feel a bit better disposed towards them (until tomorrow, that is).